| NSPM in English | |||

Surveying Turkish Influence in the Western Balkans |

|

|

|

| четвртак, 02. септембар 2010. | |

|

(Stratfor, 01.09.2010)

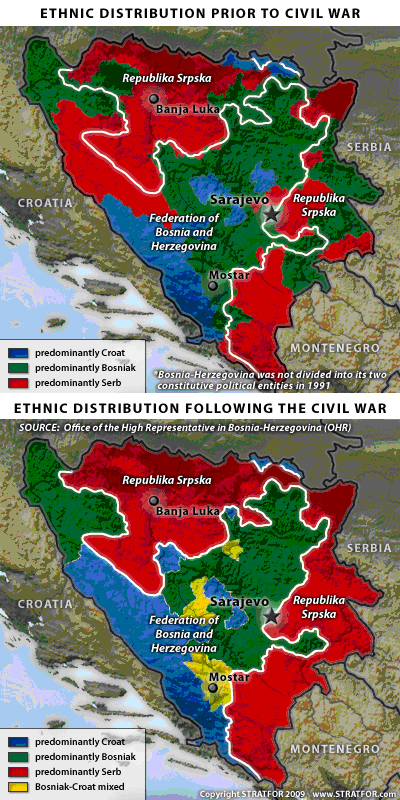

Turkish President Abdullah Gul will visit Bosnia-Herzegovina from Sept. 2-3, amid rising tensions in the lead-up to Bosnian elections. Turkey has been able to use tensions among Bosnia-Herzegovina’s ethnic groups to exert influence in the Western Balkans by acting as mediator. This is part of Turkey’s plan to reassert itself geopolitically and show Europe that without Turkey, the Western Balkans will not see lasting political stability. However, Turkey’s efforts face several obstacles, including a weak economic presence in the Western Balkans, suspicion inside the region about Ankara’s motives, and growing concerns in the West about Turkey’s power. Analysis Turkish President Abdullah Gul will pay an official visit to Bosnia-Herzegovina from Sept. 2-3. The visit comes amidst largely expected rising nationalist rhetoric in the country due to the upcoming Oct. 3 general elections. Milorad Dodik, premier of Serbian entity Republika Srpska (RS), has again hinted that RS might consider possible independence, prompting the Bosniak (Slavic Muslims from the Western Balkans) leadership to counter by calling for RS to be abolished. Meanwhile, Croat politicians continue to call for a separate ethnic entity of their own, a potential flash point between Croats and Bosniaks. Amidst the tensions between Bosnia-Herzegovina’s ethnic factions — as well as between the countries of the Western Balkans — Ankara has found an opportunity to build up a wealth of political influence in the region by playing the role of moderator. As such, Turkey is both re-establishing its presence in the region it dominated during the Ottoman Empire and attempting to become the main arbiter on conflict resolution in the region, thus obtaining a useful lever in its relationship with Europe. Ultimately, the Balkans are not high on Turkey’s list of geopolitical priorities. Turkey has much more immediate interests in the Middle East, where the ongoing U.S. withdrawal from Iraq is leaving a vacuum of influence that Turkey wants to fill and use to project influence throughout its Muslim backyard, and in the Caucasus, where competition is slowly intensifying with Russia. The Balkans rank below these, but are very much on Turkey’s mind, especially as the Balkans relate to Ankara’s relationship with Europe. However, three major factors constrain Turkey’s influence in the Balkans: a paltry level of investment on the part of the Turkish business community, suspicion from a major group in the region (Serbs) and Turkey’s internal struggle with how best to parlay the legacy of Ottoman rule into an effective strategy of influence without stirring fears in the West that Ankara is looking to recreate the Ottoman Empire. Turkey’s History in the Balkans The Ottoman Empire dominated the Balkans between the 14th and early 20th centuries, using the region as a buffer against the Christian kingdoms based in the Pannonian Plain — namely the Hungarians, and later Austrian and Russian influences. The Eastern Balkans, particularly the Wallachia region of present-day Romania, was a key economic region due to the fertile Danube basin. But the Western Balkans — present-day Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Albania — were largely just a buffer, although they also provided a key overland transportation route to Central Europe, which in the latter parts of Ottoman Empire led to growing economic importance. Twentieth century Turkey lost the capacity to remain engaged in the Balkans. It was simple to jettison the Western Balkans as dead weight in the early 20th century, as the region’s lack of resources and its status as a buffer kept the region from becoming fully assimilated. Later, Ankara lacked the capacity and the will to project power into the Balkans. Following the world war period, the Turkish republic was dominated by a staunchly secularist military, which largely felt that the Ottoman Empire’s overextension into surrounding regions led to the empire’s collapse and that attention needed to be focused at home. Essentially, Turkey was founded on European-styled nationalism and rejected non-Turkic peoples. Turkey felt little attachment to the Balkan Slavic Muslim population left behind by the legacy of the Ottoman Empire. The Balkan wars of the 1990s, however — particularly the persecution of the Muslim population of Bosnia-Herzegovina — awakened the cultural and religious links between Turkey and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The war in Bosnia-Herzegovina became a central domestic political issue, and Ankara became involved in 1994 by bringing the warring Croat and Muslim sides together to unify against the more militarily powerful Serbs. The Logic of Contemporary Turkish Influence in the Balkans Rising influence in the Balkans is part of Turkey’s return to geopolitical prominence under the ruling Islamic-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP). For one thing, the AKP is far more comfortable using the Western Balkans’ Muslim populations as anchors for foreign policy influence than the secular Turkish governments of the 1990s. The AKP is challenging the old Kemalist view that the Ottoman Empire was something to be ashamed of. The ruling party is actually pushing the idea that Turkey should reconcile with its Ottoman heritage. Ankara has therefore diplomatically supported the Muslim populations in the Balkans, favoring the idea of a centralized Bosnia-Herzegovina dominated by Bosniaks. Turkey also lobbied on behalf of Bosniaks during the recent Butmir constitutional reform process and was one of the first to recognize overwhelmingly Muslim Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence. In an October 2009 speech in Sarajevo — which raised eyebrows in neighboring Serbia and the West — Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu stated: “For all these Muslim nationalities in these regions, Turkey is a safe haven … Anatolia belongs to you, our Bosnian brothers and sisters. And be sure that Sarajevo is ours.”

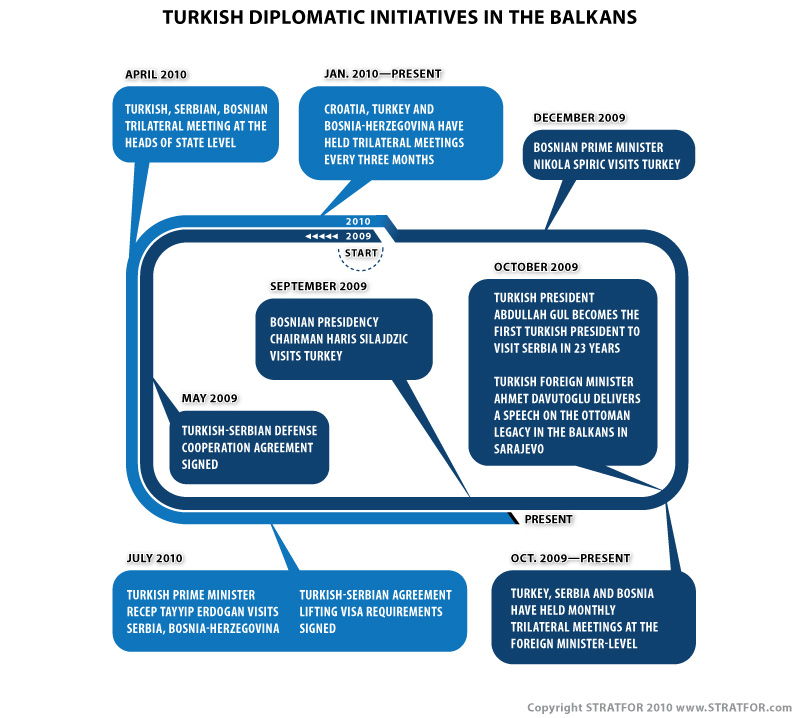

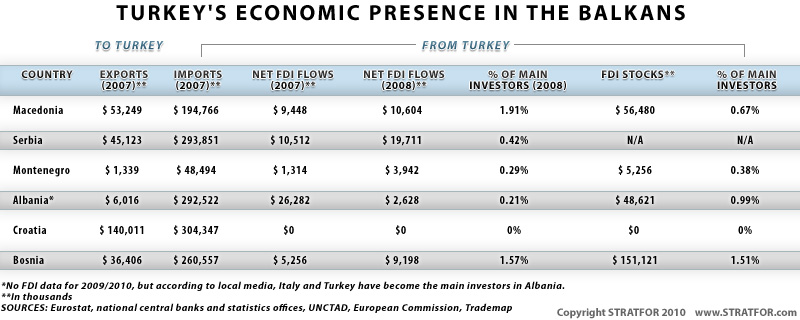

Ankara also has encouraged educational and cultural ties with the region. Turkish state-run TV network TRT Avaz recently added Bosnian and Albanian to its news broadcasting languages, while the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency has implemented several projects in the region, particularly in the educational sector. The Gulen movement — a conservative Muslim social movement — has also built a number of schools in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo. Nonetheless, Ankara has struck a balance between the natural anchoring of its foreign policy with Muslim populations that look to Turkey for leadership, and a policy of engaging all sides diplomatically (see timeline). This has led to considerable Bosniak-Serbian engagement and to regular trilateral summits between the leaders of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia. To this effect, Davutoglu also stated: “In order to prevent a geopolitical buffer zone characteristic of the Balkans, which makes the Balkans a victim of conflicts, we have to create a new sense of unity in our region. We have to strengthen the regional ownership and foster regional common sense.” Turkey wants to use its influence in the Balkans as an example of its geopolitical importance, particularly to Europe, which is instinctively nervous about the security situation in the Balkans. The point is not for Turkey to expand influence in the Balkans for the sake of influence, or for economic or political domination. Rather, Ankara wants to demonstrate that its influence is central to the region’s stability, and that without Turkey, there will be no permanent political settlement in the Western Balkans. The U.S.-EU Butmir constitutional process, as the most prominent example thus far, failed largely because Turkey lobbied the United States to step away. The message was clear to Europe: Not only does Turkey consider the Balkans its backyard (and therefore Ankara should never again be left out of negotiations), it also has the ability to influence Washington’s policy. STRATFOR sources in the European Union and the Bosnia-Herzegovina government familiar with the negotiations have indicated that the Europeans were caught off guard and displeased by just how much influence Ankara has in the region. Arrestors to Turkish Influence in the Western Balkans Although Ankara’s diplomatic influence in the region is significant, Turkey’s economic presence is not as large as often advertised by both Turkey’s supporters and detractors in the region. Bilateral trade and investments from Turkey have been paltry, especially compared to Europe’s economic presence. Turkey has also lagged in targeting strategic sectors (like energy), Russia’s strategy for penetration in the region. (However, Turkey has initiated several investments in the Serbian and Macedonian transportation sectors.) Ankara is conscious of this deficiency and plans to address it. As part of a push to increase economic involvement in the region, the Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists plans to travel with Gul to Sarajevo. However, without concrete efforts, it is difficult to gauge Ankara’s success, and Turkey’s ability to sustain political influence in the Balkans without a firm economic grounding is questionable. Another key arrester to Turkish involvement in the region is the suspicion of Ankara’s intentions among Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina. With Turkey using Bosniak interests to anchor its foreign policy in the region, RS is concerned that Ankara’s summits with Belgrade, Sarajevo and Zagreb are meant to isolate it. Similarly, nationalist opposition inside Serbia to the nominally pro-Western Serbian president, Boris Tadic, is beginning to tie rising Turkish influence in the Balkans to increased tension in the Sandzak region of Serbia, which is populated by Muslims. There is danger that a change in government in Belgrade, or domestic pressure from the conservative right, could push Tadic to distance himself from Turkey and move toward Russia, introducing a great-power rivalry (eerily reminiscent of pre-World War I). That may be more than what Ankara has bargained for. If this were to happen, it would be a major obstacle to Turkey’s strategy to showcase itself as the region’s peacemaker. In fact, a Turkish-Russian rivalry would undermine that image and greatly alarm Europeans that the Balkans are returning to their 19th-century status as a chessboard for Eurasian great powers. The use of cultural and religious ties has strengthened Turkey’s hand in the Balkans. However, the AKP is conscious of the image it is presenting to the West, where skepticism of Turkey’s commitment to secularism is increasing after recent events in the Middle East have suggested that Ankara is aligning with the Islamic world at the West’s expense (such as the recent Gaza flotilla incident). The AKP has also been dealing with an intense power struggle at home with secular elements tied to the military, which are not comfortable with Turkey’s neighbors viewing that country as neo-Ottoman or pan-Islamic. AKP therefore has to walk a thin line between anchoring its influence among the Muslim populations of the Balkans and presenting itself as a fair arbiter between all sides, while also taking care to manage its image abroad. |

Од истог аутора

- The Nabucco West Project Comes to an End

- Remaking the Eurozone in a German Image

- Serbia: A Weimar Republic?

- NATO's Lack of a Strategic Concept

- The Geopolitics of Turkey: Searching for More

- Kosovo – Consequences of the ICJ Opinion

- Kyrgyzstan and the Russian Resurgence

- Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan: A Customs Deal and a Way Forward for Moscow

- Montenegro's Membership in NATO and Serbia's Position

- ЕУ: Убрзано ширење на Балкан

- The Return of Germany

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)

Summary

Summary