| NSPM in English | |||

Russia’s New Geopolitical Energy Calculus |

|

|

|

| петак, 26. март 2010. | |

|

(Global Research, 20.3.2010)

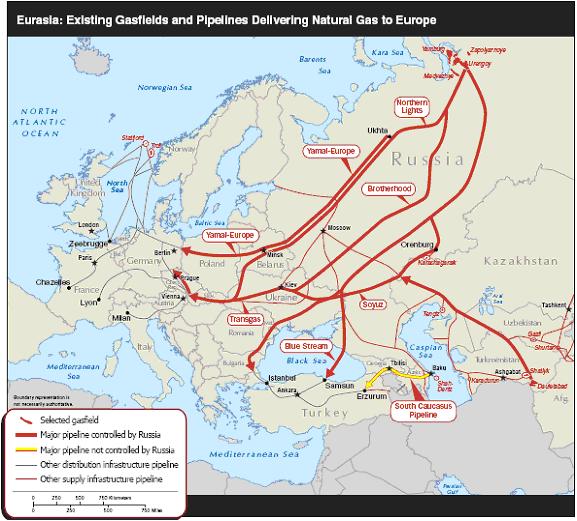

Russia’s North-South-East-West energy strategy The defusing of major Washington military threats is far from the only gain for Moscow in having a neutral but stable Ukrainian neighbor. Russia now vastly improves its ability to expand the one great power lever it has, outside of its remaining and still formidable nuclear strike force. That lever is to counter Washington’s relentless military pressure by cleverly using export of the world’s largest reserves of natural gas, a fuel much in demand in Western Europe and even in UK where North Sea fields are in decline. According to west European industry estimates, demand within the European Union countries for natural gas, especially for use in electric power generation where it is seen as a clean and very efficient fuel, is estimated to rise some 40% from today’s levels over the next twenty years. That increase in gas demand will coincide with a decline in current gas output from fields in the UK, Netherlands and elsewhere in the EU.[1] With Ukraine’s shift from hostile opposition to Moscow to what Yanukovych terms ‘non-aligned’ neutrality - with an early emphasis on stabilizing Russian-Ukrainian gas geopolitics - Moscow suddenly holds a far stronger array of economic options with which to neutralize Washington’s game of military and economic encirclement. When Yushchenko and Georgia's Saakashvili took the reins of power in their respective countries and began taking steps with Washington to join NATO, one of the few means available for Putin’s Russia to re-establish some semblance of economic security was its energy card. Russia has by far the world's largest known reserves of natural gas. Interestingly, according to US Department of Energy estimates, the second largest gas reserves are in Iran, a country also high on Washington's target list.[2] Today, Russia is clearly pursuing a fascinating, highly complex multi-pronged energy strategy. In effect it is using its energy as a diplomatic and political lever to ‘win friends and influence (EU) people.’ Putin’s successor as President, Dmitry Medvedev, is well suited to the role of overseeing gas pipeline geopolitics. Before becoming Russian President, he had been chairman of the state-owned Gazprom. High-stakes Eurasian chess game In a sense, the Eurasian land area today resembles a geopolitical game of three-dimensional chess between Russia, the European Union member countries, and Washington. The stakes of the game are a matter of life and death for Russia as a functioning nation, something clearly Medvedev and Putin well realize at this point. US attempts at the military encirclement of Russia included not only the Rose and Orange Revolutions in 2003 and 2004, but also the highly provocative Pentagon missile ‘defense’ policy of placing US-controlled (not NATO-controlled) missiles in key former Warsaw Pact countries on Russia’s direct perimeter. As a result, Moscow has developed a remarkable and complex energy pipeline strategy to undercut a clearly hostile US military strategy that has used NATO encirclement, missile deployments, and ‘color revolutions,’ including the attempted destabilization of Iran during summer 2009 with a ‘Green Revolution’ or what Hillary Clinton flippantly dubbed the ‘Twitter Revolution.’ All of these US moves have attempted to isolate Russia and weaken her potential strategic allies across Eurasia. For Russia, which recently surpassed Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer and exporter, sales of its natural gas abroad has a significant advantage in that Moscow is better able to control the price and market of gas. Unlike oil, whose price is tightly controlled by a cartel of Big Oil (and their Wall Street co-conspirators such as Goldman Sachs, Morgn Stanley, JP MorganChase), natural gas is far more difficult for Wall Street to manipulate on a short-term speculative basis as with oil. Because gas, unlike oil, is dependent on construction of costly pipelines or LNG tankers and LNG port terminals, it tends to have a price fixed by bilateral long-term agreements between buyer and seller. That gives Moscow a degree of protection against events such as the brazen Wall Street manipulation of oil prices in 2008-2009 from a record high of $147 a barrel down to below $30 only months later, manipulations which devastated Moscow’s oil earnings at just the time the global financial crisis cut off credit to Russian banks and companies. With Yanukovych now President in Ukraine, the way appears clear for a rational gas supply and transit contract from Russia’s Gazprom to and through Ukraine, and continuing on to western Europe. Fully half of Ukraine’s domestic energy comes from natural gas and the overwhelming bulk of that gas, some 75%, comes from Russia.[3] At this point it seems a stable settlement has been reached between the Russian and Ukrainian governments on pricing for imported Russian gas. As of January 2010 Ukraine has agreed to pay prices close to western European levels for its gas, and at the same time she will get significantly higher transit fees from Russia’s state-owned Gazprom for transporting Russian gas through to western Europe. Some 80% of Russian gas exports went through Ukraine up until now.[4] That’s about to change dramatically however, with the implementation of Russia’s long-term pipeline strategy, a strategy designed to make Russia less vulnerable to future political shifts such as the 2004 Ukraine Orange Revolution.

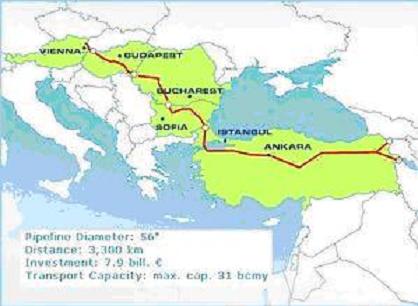

Nord Stream was especially vital for Russia when it looked possible that Washington might succeed in pulling Ukraine into NATO after the Orange Revolution. Today the alternative Baltic Sea pipeline assumes a different importance for Russia. The Nord Stream gas pipeline from Russia’s port of Vyborg near St. Petersburg to Greifswald in northern Germany, goes beneath the Baltic Sea in international waters, completely bypassing both Ukraine and Poland. When Nord Stream was announced as a joint venture between two major German gas companies, E.ON and BASF with Russia’s Gazprom, and with former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder as board member, Sikorski, then Poland's Defense Minister, compared the German-Russian gas deal to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact -- the 1939 pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which divided Poland between the two.[5] Sikorski’s logic was not so precise but his emotional imagery was. In late 2009 Sweden and Finland joined Denmark in finally granting passage rights through their portion of the Baltic Sea for the pipeline. Construction of the multi-billion dollar project is due to begin this April and gas deliveries are to begin in 2011. When a second parallel pipeline, due to start construction in 2011, is completed, Nord Stream anticipates a full capacity of 55 billion cubic meters of gas a year, enough to fuel 25 million households in Europe, according to the Nord Stream website. With Nord Stream’s primary gas route directly from Russia to its major clients in Germany, along with a stable transit agreement through Ukraine, the likelihood of a disrupted supply of Gazprom deliveries to northern Europe becomes remote. Nord Stream will allow Moscow’s Gazprom to use a more flexible gas diplomacy and to greatly lessen future vulnerability to transit country supply disruptions such as it has had in recent years from a hostile Ukraine. At the end of 2009 in Minsk, just as Nord Stream was clearing the final political hurdles, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev met with Belarus officials. Medvedev said that Russia was considering a second leg of its large Yamal-Europe gas pipeline through Belarus if future demand from western Europe warranted, stating, “I think the more possibilities there are for Russian gas supplies to Europe, the better it will be for both Europe and Russia.”[6] In addition, in a notable geopolitical shift, the UK has just signed a long-term contract with Gazprom to import gas via the Nord Stream to meet more than 4% of UK gas demand by 2012, as Britain shifts from being a gas exporter to a gas importer.[7] Presently, in addition to the UK and Germany, Gazprom now has contracts to supply Denmark, The Netherlands, Belgium and France, making it a major new factor on the EU energy supply market. South Stream strategy Meanwhile, Washington, bitterly opposed to Nord Stream, attempted unsuccessfully to block it by proxy through back-door support for Poland and other EU opposition. In a second major front in what could be called the Russia-USA pipeline wars, the US has initiated competing proposals to build gas pipelines to serve the countries of southern and southeastern Europe. Here Washington is openly backing what is called the Nabucco pipeline project. Moscow is promoting what it calls its South Stream project, the southern Eurasian sister to the Nord Stream in the north of Europe. On December 12, 2009 the government of Bulgaria, a former Warsaw Pact member now in NATO and the EU, announced that it would participate in Moscow’s South Stream project despite considerable pressure from Washington. In June 2007, Gazprom and Italy’s ENI concern signed a Memorandum of Understanding for the South Stream project to design, finance, construct and manage the South Stream. ENI, Italy’s largest industrial company, created in the 1950’s by Italy’s legendary Enrico Mattei, is also partly state-owned and has been involved in the Russian gas business since the early 1970’s. South Stream’s offshore section is to run under the Black Sea from the Russian coast to the Bulgarian coast, a length of around 550 miles at a maximum depth over two kilometers and have a full capacity of 63 billion cubic meters, even larger than Nord Stream. From Bulgaria, South Stream will split into two arms, the northern section stretching to Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Austria and the southern arm going through Bulgaria to southern Italy. The new pipeline is expected to become operational in 2013. Gazprom has an agreement to provide Italy with gas until 2035 and South Stream will be the main vehicle for that. South Stream AG, the 50-50 Gazprom-ENI joint venture is registered in Switzerland. To date Gazprom has signed transit agreements for the pipeline with the Republic of Serbia and Greece and Hungary.[8] In January 2008, Gazprom bought 51% of the Serbian state oil monopoly NIS to secure its presence there. An indication of the pressure that Washington has put on Bulgaria over its participation in Russia’s South Stream is that Bulgaria also signed up to take part in the Nabucco project in December 2009. Commenting on the dual signings, Bulgaria’s Prime Minister Boyko Borisov told the press, “Nabucco is a priority of the European Union while the Russian South Stream is moving forward very quickly and many European countries are joining it almost daily.”[9] On March 3, 2010 the new Croatian government of Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor signed an agreement in Moscow with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin allowing the pipeline to pass through Croatian territory, setting up a 50-50 joint venture to realize the construction. Kosor said that the agreement ‘On the Construction and Exploitation of a Gas Pipeline on Croatian Territory’ creates a legal basis for Croatia's involvement in South Stream, allowing the parties to set up a 50/50 joint venture. Two days later, in what seemed a snowballing enthusiasm for Gazprom’s project, the Bosnian Serb Republic announced that it, too, will join the South Stream gas pipeline project. It proposes to build a 480 km pipeline in northern Bosnia and link it to the South Stream pipeline, bringing the total number of participating countries that have signed deals with Gazprom to seven.[10] In addition to Serb Bosnia, Gazprom’s partners now include Bulgaria, Hungary, Greece, Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. It almost retraces the Balkan route of the controversial Berlin-to-Baghdad railway which played such a decisive geopolitical role in British machinations that ultimately led to World War I following the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, Archduke Francis Ferdinand.[11] The central issue for the two competing pipeline projects, South Stream and Nabucco, is not who will buy their gas. As noted, natural gas demand across Europe is expected to rise dramatically in coming years. Rather it’s the question of where the gas will come from to fill the pipeline. Here Moscow now clearly holds the trump cards. In addition to gas directly from Russia’s gas fields, a major component of South Stream gas is to come from Turkmenistan and from Azerbaijan and possibly at some point from Iran. In December 2009 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev went to Turkmenistan to sign major agreements on energy cooperation. Until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Turkmenistan was a republic of the Soviet Union, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic, Turkmen SSR. It is bordered by Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest, Uzbekistan to the east and northeast, Kazakhstan to the north and northwest and the Caspian Sea to the west. Russia’s Gazprom until now has been the dominant economic partner of the country, which has newly confirmed huge gas reserves. Turkmen gas has been vital for the supply chain of Gazprom and dates back to the era when Turkmenistan was an integral part of the Soviet Union and the Soviet economic infrastructure. When ’President for Life,’ Saparmurat Niyazov, known as ‘Türkmenbaşy’ or ‘leader of the Turkmens,’ died unexpectedly in December 2006, Washington began entertaining hopes of weaning the new President, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, away from Russia and into the US orbit. To date they have met with little success. The Medvedev-Berdimuhamedow December agreements included new agreements for Turkmen long-term gas supplies to Gazprom which will fill the South Stream pipeline either directly or by replacing Russian gas to the same -- meaning Nabucco is left out in the cold there. Nabucco high and dry... The active pipeline diplomacy of Russia and Gazprom in recent months has dealt a devastating blow to Washington’s favored alternative, Nabucco, which is planned to run from the Caspian region and Middle East via Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary with Austria and further on to Central and Western European gas markets, some 3,300 km, starting at the Georgian-Turkish and/or Iranian-Turkish border. End station would be Baumgarten in Austria. The project is parallel to the existing US-backed Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum oil pipeline and could transport 20 billion cubic meters of gas a year. Two-thirds of the pipeline would pass through Turkish territory. Following a two day visit to Ankara in April 2009, US President Obama appeared to have won a major victory for Nabucco when Turkey’s President Erdogan agreed to sign on to the project in July 2009, after several years of delay. Nabucco is an integral part of a US strategy of total energy control over both the EU and all Eurasia. It explicitly has been conceived to run entirely independent of Russian territory and is aimed at weakening the energy ties between Russia and Western Europe. Those energy ties were considered a significant reason why the German government along with France refused to back Washington’s push to bring Ukraine and Georgia into NATO. Today the future of Nabucco is in grave doubt. The problem is that Russia’s Gazprom has all but locked up long-term gas contracts with all the potential suppliers of gas for Nabucco, leaving Nabucco high and dry. Thus, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Iraq are being touted as potential suppliers to Nabucco. Until now the main gas supply for Nabucco should be Azerbaijan, the source of large oil reserves captured by a BP-led Anglo-American consortium bringing Baku oil from the Caspian Sea to the west, independent of Russia. That Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline was a major reason Washington backed the 2004 Georgian ‘Rose Revolution’ that put dictator Mikhail Saakashvili into power. In July 2009 Russia’s Medvedev and Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller went to Baku and signed a long-term contract to buy all the gas from the Azeri Shah Deniz-2 offshore field, the same field Nabucco hopes to tap for its pipeline. Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev seems to be playing a cat-and-mouse game with both Russia and EU-Washington, to play one off against the other for the highest price. Gazprom agreed to pay an unusually high price of $350 per thousand cubic meters for their Shah Deniz gas, a clear political not economic decision by Moscow that owns controlling interest in Gazprom.[12] In early January 2010, the Azeri government also announced sale of a portion of its gas to neighboring Iran, another blow to Nabucco supply.[13]

Even were Azerbaijan to agree to sell gas and Nabucco to buy it on competitive terms to Gazprom, industry sources say the Azeri gas alone would not suffice to fill the pipeline. Where could the remaining gas come from? One possible answer is Iraq; the second is Iran. Both would entail huge geopolitical problems for Washington, to put it mildly. Currently, even a minimal agreement between Turkey and Azerbaijan for delivery of Azeri gas to Nabucco is in serious doubt. Despite the highly publicized Turkish government decision in 2009 to finally join Nabucco, the vital talks between Turkey and the Azeri government remain stalemated. Despite repeated interventions from US Special Envoy on Eurasian Energy Richard Morningstar to force a final deal, talks remain deadlocked as of this writing. Adding to the woes of Washington’s Nabucco dreams, one of the key partners of the Nabucco, Austria’s OMV, told the Dow Jones wire service at the end of January that the Nabucco pipeline would not be built if demand is too low.[14] In terms of other options being proposed by some in Washington, for Iraqi gas to flow into Nabucco it would have to go through the Kurdish regions of both Iraq and of Turkey, giving the Kurdish minorities a potential major new revenue source, something not so very welcome in Istanbul. Iran as a potential gas source is at present not in the Washington calculus because of the tensions over Iranian nuclear plans, but more because of Iran’s enormous influence over the future of Iraq, where they exercise significant influence on the majority Shi’ite population there. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, though both have significant natural gas reserves, are even more politically and geographically unlikely as sources of gas for essentially an anti-Russian project. Their distance would mean skyrocketing costs, pricing it far above gas from Gazprom’s South Stream. In a true exercise of Byzantine diplomacy, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan invited both Russia and Iran to join the Nabucco project. According to RIA Novosti, Erdogan stated, “We want Iran to join the project when conditions will allow, and also hope for Russia’s participation in it.” Then, just weeks after a formal signing of the Nabucco agreement with the US, during Putin's visit to Ankara in August 2009, Turkey granted Russia's state-run natural-gas monopoly Gazprom use of its territorial waters in the Black Sea, where Moscow wants to route its South Stream pipeline to deliver gas to Eastern and Southern Europe. In exchange, Gazprom agreed to build a pipeline across Turkey from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.[15] In early January 2010, the Turkish government furthered its growing ties with Russia during a two day visit to Moscow by Prime Minister Erdogan during which energy and the South Caucasus were discussed. Washington’s Radio Liberty calls it a “new strategic alliance“ between the once-bitter Cold War rivals. Significantly, Turkey is also in NATO.[16] This is no passing fad. Press in both countries speak openly of a Russo-Turkish “strategic partnership.“[17] Today Turkey is Russia’s largest market for export of Russian oil and gas combined. As well the two countries are discussing plans for Russia to build Turkey’s first nuclear power plant to meet Turkey’s electricity demand. Bilateral Turkish-Russian trade last year reached $38 billion making Russia Turkey’s largest trade partner. The figure is expected to grow some 300% over the next five years, creating a solid and expanding pro-Russia trade lobby in Turkey. The two countries are in detailed negotiation over some $30 billion in new trade agreements, including Turkey’s nuclear power plant, as well as the South Stream, Blue Stream Turkish-Russian gas pipelines and a Samsun-Ceyhan oil pipeline from Russia to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast.[18] Indicating how many land mines could explode in the face of Nabucco’s backers, especially in Washington, the Turkish parliament on March 4, 2010 approved a bill on the construction of the Nabucco pipeline. But the same day the US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee passed a non-binding resolution calling the World War I-era killing of Armenians genocide. The vote led to the immediate recall of Turkey’s Ambassador to Washington as a protest, and will possibly lead to even closer cooperation between Moscow and Ankara on matters of mutual interest, including South Stream. The European Union has just approved a $3 billion general economic stimulus that includes $273 million for Nabucco. At an estimated final cost of $11 billion, that is hardly convincing support for Nabucco. Moreover, the money is being frozen until a final go-ahead for Nabucco is clear, indicating that the countries of the EU are hardly as eager as Washington to back the risky Nabucco counter to Moscow’s South Stream. The EU has said if there is no firm agreement between Nabucco backers and Turkmenistan for gas supply within six months, the money will be used for other projects.[19] The combination of neutralizing the threat of Ukraine in NATO, starting construction of the strategically important Nord Stream Russian pipeline to Germany and westwards, and Russia advancing its South Stream gas pipeline plans has effectively rendered Washington’s Nabucco pipeline counter-strategy impotent. These developments ensure that Russia’s role as Europe’s largest energy supplier is secure. In recent years Russia has grown to become the source for almost 30% of EU oil imports and by far the largest share of its natural gas.[20] That has enormous strategic geopolitical significance, a point not missed in Washington. However, with its role in Europe seemingly shored up and the Orange Revolution de facto rolled back, Russia’s policymakers are increasingly turning to the east and the energy demands of its cooperation partner and former Cold War foe, China. Moscow Goes East At the end of 2009, precisely as planned and to the surprise of Washington, Russia opened the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline, a four-year construction project costing some $14 billion. The pipeline now allows Russia to export oil directly from its East Siberia fields to China as well as South Korea and Japan, a major step in closer economic integration between especially Russia and China. The pipe now runs to Skovorodino just north of the Chinese border on the Bolshoy Never River. From here at present the oil is loaded onto rail tank cars for transport to the Pacific port of Kozmino near Vladivostok. The port alone cost $2 billion to build, has capacity to handle 300,000 barrels of crude per day, with oil quality comparable to that of Middle Eastern oil blends now dominating the market. Transneft, the Russian state pipeline monopoly, spent another $12 billion to lay the 2,700-km ESPO pipeline through east Siberian wilderness, to connect the area's various oil fields being developed by Russian oil majors Rosneft, TNK-BP and Surgutneftegaz. The final link of pipeline to the port of Kozmino is due to be completed in 2014, costing an added $10 billion and resulting in a pipeline almost 4800 kilometers long, a distance greater than from Los Angeles to New York. Moscow and Beijing have also agreed to build a spur pipeline from Skovorodino to Daqing in China’s Heilongjiang province in northeastern China, the center of its energy and petrochemical industry and site of China’s largest oilfield. When completed, the pipeline will carry eastward an annual 80 mm tons of oil from Siberia, including 15 mm tons to China through an additional spur. An indication of the priority that energy-hungry China places on Russian oil, China has loaned $25 billion to Russia in exchange for oil deliveries over the next two decades. In February 2009, when world oil prices dropped to $25 a barrel from a record high $147 some six months before, Russian oil giant Rosneft and pipeline operator Transneft were on the brink of collapse. Beijing, in a deft and swift move to insure future oil from Russia’s East Siberia fields, stepped in and through the state-owned Chinese Development Bank offered loans to Rosneft and Transneft of $10 billion and $15 billion respectively, a $25 billion dollar investment to accelerate the construction of the pacific pipeline. For its part, Russia agreed to develop further new fields, build the ESPO leg for Daqing from Skorovodino to the Chinese border, a distance of some 43 miles, and supply China with at least 300,000 barrels of highly in-demand sweet or low sulfur crude oil per day.[21] Beyond the Russian border, in the Chinese interior, Beijing will construct a domestic pipeline approximately 600 miles long to Daqing. The Chinese loan was made at 6% interest and would require Russian oil be sold to China for $22 per barrel. Today the average international oil price has recovered to some $80 a barrel, meaning China has locked in a golden prize. Rather than reneg on the price deal, Moscow has clearly decided the strategic advantages of the China link outweigh possible revenue loss. It retains price control over the rest of the oil flowing through the ESPO pipeline on to the Pacific for other Asian markets. Whereas the energy markets of Western Europe pose a relatively stagnant demand prospect, those of China and Asia are booming. Moscow is making a major shift eastwards in light of that fact. At the end of 2009, the Russian government released a comprehensive energy report entitled “Energy Blueprint for 2030.” It calls for substantial domestic investment in the East Siberian fields, and speaks of a shift in oil exports toward Northeast Asia, with the share of the Asia Pacific region in Russian exports growing from 8% in 2008 to 25% over the next years.[22] That will have significant political consequences for both Russia and Asia, especially China. China passed Japan several years ago to become the world’s second major oil importing nation after the United States. The issue of Chinese energy security is of such paramount importance for China that Prime Minister Wen Jaibao has just been named to head a cross-ministry National Energy Council to coordinate all issues of China’s energy policy.[23] Russian begins LNG deliveries for Asia A few months before the completion of the ESPO oil pipeline to the Pacific, Russia began its first ever deliveries of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) from the Gazprom-led Sakhalin-II project, a joint venture that includes Japan’s Mitsui and Mitsubishi as well as the Anglo-Dutch Shell. For Russia the project will give her invaluable experience in the rapidly expanding global LNG market, a market not dependent on fixed long-term pipeline construction. China has also made forays into other countries in the former Soviet Union area to secure its energy needs. Late in 2009 the first stage of a pipeline, known variously as the Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline or the Turkmenistan–China Gas Pipeline, was completed. It brings natural gas from Turkmenistan across Uzbekistan to southern Kazakhstan parallel to the existing Bukhara-Tashkent-Bishkek-Almaty pipeline.[24] Within China, the pipeline connects with the existing West-East Gas Pipeline that crosses China and supplies cities as far as Shanghai and Hong Kong. Some 13 billion cubic meters (bcm) are supposed to go through the pipeline in 2010, increasing to over 40 bcm by 2013. Ultimately the pipeline could supply more than half of China’s current natural gas consumption. It marked the first pipeline to bring Central Asian natural gas to China. The pipeline from Turkmenistan will be connected to a branch line from western Kazakhstan, scheduled to open in 2011 and which will supply natural gas from several Kazakh fields to Alashankou in China’s Xinjiang Province.[25] Little wonder that Chinese authorities were none too pleased with ethnic Uighur riots in July of 2009, which the Chinese government claimed was instigated by the Washington-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC) and its leader Rebiya Kadeer, who reportedly has close ties to the US Congress’ regime-change NGO, the National Endowment for Democracy.[26] Xinjiang is becoming ever more strategically important to future Chinese energy flows. Far from a threat to Russia’s energy strategy as some western commentators claim, the Turkmen-China gas pipeline in effect serves to deepen the economic ties within the countries of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, SCO, at the same time it locks up for China a major portion of Turkmen gas that might have gone to the floundering Nabucco pipeline favored by Washington. That can only be to the geopolitical advantage of Russia which would lose a major economic influence were Nabucco to succeed. The SCO, founded in 2001 in Shanghai by the heads of state of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, has evolved into what might be called Halford Mackinder’s worst nightmare—a vehicle for welding close economic and political cooperation of the key Eurasian land powers independently of the United States. In his widely-publicized 1997 book, The Grand Chessboard, former US National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski bluntly stated, “It is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges capable of dominating Eurasia and thus of also challenging America. The formulation of a comprehensive and integrated Eurasian geostrategy is therefore the purpose of this book.”[27] He added the warning, “Henceforth, the United States may have to determine how to cope with regional coalitions that seek to push America out of Eurasia, thereby threatening America's status as a global power.”[28] In the wake of the events of September 2001, events which many Russian intelligence experts doubted to be the work of a rag-tag band of Muslim Al Qaeda fanatics, the SCO has begun to take the character of the very threat that Brzezinski, a student of Mackinder, warned of. In a recent interview on The Real News, Brzezinski also bemoaned the lack of any coherent Eurasian strategy, notably in Afghanistan and Pakistan, on the part of the Obama Administration. Russia also moves North to the Arctic Circle Completing Russia’s new geopolitical energy strategy, the remaining move is to the north, in the direction above the Arctic Circle. In August 2007, then-Russian President Vladimir Putin caught the notice of NATO and Washington when he announced that two Russian submarines had symbolically planted the Russian flag at a depth of over 4 kilometers on the Arctic Ocean floor, laying claim to the seabed resources. Then in March 2009 Russia announced that it would establish military bases along the northern coastline. New US NATO Supreme Commander Admiral James Stavridis expressed concern that Russian presence in the Arctic could pose serious problems for NATO.[29] In April 2009, the state-owned Russian news service RIA Novosti reported that the Russian Security Council had published an official policy paper on its Web site titled, "The fundamentals of Russian state policy in the Arctic up to 2020 and beyond." The paper described the principles guiding Russian policy in the arctic, saying it would involve establishing significant Russian army, border and coastal guard forces there "to guarantee Russia's military security in diverse military and political circumstances," according to the report.[30] In addition to staking claim to some of the world’s largest untapped oil and gas resources, Russia is clearly moving to pre-empt a further US expansion of its misleadingly named missile ‘defense’ to the Arctic Circle in echoes of the old Cold War era. Last September Dmitry Rogozin, Russia's envoy to NATO, told Vesti 24 television channel that the Northern Sea Route through the Arctic might provide the United States with an effective theater to position shipboard missile defenses to counter Russian weapons. His remarks followed the announcement by US President Barack Obama that the US would place such defenses on cruisers as a more technically advanced alternative.[31] A 2008 estimate by the US Government’s US Geological Survey (USGS) concluded that the area north of the Arctic Circle contains staggeringly large volumes of oil and natural gas. They estimated that more than 70% of the region’s undiscovered oil resources occur in five provinces: Arctic Alaska, Amerasia Basin, East Greenland Rift Basins, East Barents Basins, and West Greenland-East Canada. More than 70% of the undiscovered natural gas is believed located in three provinces, the West Siberian Basin, the East Barents Basins, and Arctic Alaska. Some 84% of the undiscovered oil and gas occurs offshore. The total undiscovered conventional oil and gas resources of the Arctic are estimated to be approximately 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.[32] The main potential beneficiary is likely to be Russia which has the largest share of territory in the region. Contrary to widely held beliefs in the west, the Cold War did not end with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 or the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, at least not for Washington. Seeing the opportunity to expand the reach of US military and political power, the Pentagon began a systematic modernization of its nuclear arsenal and a step-wise extension of NATO membership right to the doorstep of Moscow, something that then-Secretary of State James Baker III had pledged to Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev would not happen.[33] Washington lied. During the chaos of the Yeltsin years, Russia’s economy collapsed under IMF-mandated ‘shock therapy’ and systematic looting by western companies in cahoots with a handful of newly created Russian oligarchs. The re-emergence of Russia as a factor in world politics, however weakened from the economic shocks of the past two decades, has been based on a strategy that obviously has drawn from principles of asymetric warfare, economic as well as military. Russia’s present military preparedness is no match for the awesome Pentagon power projection. However, she still maintains the only nuclear strike force on the planet that is capable of posing a mortal threat to the military power of the Pentagon. In cooperation with China and its other Eurasian SCO partners, Russia is clearly using its energy as a geopolitical lever of the first order. The recent events in Ukraine and the rollback there of the ill-fated Washington Orange Revolution, in the context now of Moscow’s comprehensive energy politics, present Washington strategists with a grave challenge to their assumed global “Full Spectrum” dominance. The US debacle in Afghanistan and the uneasy state of affairs in US-occupied Iraq have done far more than any Russian military challenge to undermine the global influence of the United States as sole decision maker of a ‘unipolar world.’ http://www.globalresearch.ca /index.php?context=va&aid=18129 [1] Eurogas (European Union of the Natural Gas Industry), Natural Gas Demand and Supply: Long-Term Outlook to 2030, Brussels, Belgium, 2007, accessed in www.eurogas.org/... /Eurogas%20long %20term%20outlook %20to% 202030%20-%20fina... [2] Jim Nichol, op. cit. [3] US Department of Energy, Ukraine Country Analysis Brief, Energy Information Administration, August 2007, Washington DC, accessed in http://www.eia. doe .gov /cabs /Ukraine /Full.html [4] International Energy, Russia to supply 116 bn cm of gas to Europe via Ukraine in 2010, Beijing, November 19, 2009, accessed in http://en.in-en.com [5] Simon Taylor, Why Russia's Nord Stream is winning the pipeline race, January 29, 2009, EuropeanVoice.com, accessed in http://www.europeanvoice.com /article/imported /why- russia%E2%80%99s- nord- stream-is- winning-the -pipeline-race/63780.aspx [6] RAI Novosti, Russia pledges 30-40% discount on gas for Belarus in 2010, November 23, 2009, accessed in http://en.rian.ru [7] UPI, Nord Stream to supply UK by 2012, December 1, 2009, accessed in http://www.upi.com [8] Gazprom, Major Projects: South Stream, accessed in http://old.gazprom.ru /eng /articles /article27150.shtml [9] Trend, Bulgaria ready to participate in both South Stream and Nabucco, Baku, Azerbaijan, December 5, 2009, accessed in http://en.trend.az [10] Olja Stanic, Bosnian Serbs to join Russia-led gas pipeline, Reuters, March 5, 2005, Banјa Luka Bosnia, accessed in http://in.reuters.com /article /oilRpt /idINLDE6241 B920100305 [11] For more on this fascinating and all-but-forgotten history of the German-British imperial rivalries over the Berlin-Baghdad Railway project in the prelude to the First World War, see, F. William Engdahl, A Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order, London, Pluto Press, 2004, pp. 22-28. [12] Mahir Zeynalov, Azerbaijan-Gazprom agreement puts Nabucco in jeopardy, Today’s Zaman, July 16, 2009, accessed in http://www.todayszaman.com /tz-web /sabit.do?sf=aboutus [13] Saban Kardas, Delays in Turkish-Azeri Gas Deal Raises Uncertainty Over Nabucco, Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol. 7 Issue 39, February 26, 2010. [14] Ibid. [15] Brian Whitmore, Moscow Visit by Turkish PM Underscores New Strategic Alliance, Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe, January 13, 2010, accessed in http://www.rferl.org /content/Moscow_Visit_By_Turkish_PM_Underscores_New_S trategic_Alliance /1927504.html [16] Ibid. [17] Faruk Akkan, Turkey and Russia move closer to building strategic partnership, RAI Novosti, January 15, 2010, accessed in http://en.rian.ru/valdai_foreign_media/20100115/157554880.html [18] RAI Novosti, Russian delegation to discuss Turkey nuclear power plant plan, Ankara, Febr. 18, 2010, accessed in http://en.rian.ru/world/20100218 /157927131.html [19] Kommersant, Nabucco's future depends on Turkmenistan, Moscow, March 9, 2010, accessed in http://en.rian.ru/papers/20100309/158135872.html [20] US Energy Information Administration, Russia: Oil Exports, accessed in http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu /cabs /Russia/Oil_exports.html [21] Greg Shtraks, The Start of a Beautiful Friendship? Russia begins exporting oil through the Pacific port of Kozmino, Jamestown Foundation Blog, Washington D.C., December 11, 2009, accessed in http://jamestownfoundation. blogspot.com /2009 /12 / start-of-beautiful- friendship-russia.html [22] Ibid. [23] Moscow Times, Putin Launches Pacific Oil Terminal, December 29, 2009, accessed in http://www.themoscowtimes.com [24] Zhang Guobao, Chinese Energy Sector Turns Crisis into Opportunities, January 28, 2010, accessed in www.chinadaily.com.cn [25] Isabel Gorst, Geoff Dyer, Pipeline brings Asian gas to China, London, Financial Times, December 14, 2009. [26] Reuters, China calls Xinjiang riot a plot against its rule, 5 July 2009, accessed in http://www.reuters.com /article/idUSTRE56500R20090706 [27] Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and It's Geostrategic Imperatives, New York, Basic Books, 1998 (paperback), p. xiv. [28] Ibid., p.55. [29] UPI.com, Russia’s Arctic Circle Claims Worry NATO, October 2, 2009, accessed in http://www.upi.com/Top_News/2009/10/02/Russias-Arctic-Circle-claims-worry-NATO/UPI-55371254525955/ [30] Mark Sieff, Russia creating new armed forces to boost power in arctic, UPI.com, April 6, 2009, accessed in http://www.upi.com /Business_News /Security-Industry /2009/04/06 /Russia-creating-new-armed-forces-to-boost-power- in-arctic/UPI-88341239045539/ [31] UPI.com, Russia fears missile defenses in Arctic, September 29, 2009, accessed in http://www.upi.com/Top_New s/2009/09 /29 /Russia-fears-missile- defenses- in-Arctic /UPI-80901254231286/ [32] Donald L. Gautier, et al, USGS Arctic Oil and Gas Report: Estimates of Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle, Washington D.C., USGS, July 2008, accessed in http://geology.com /usgs/arctic-oil-and-gas- report.shtml [33] F. William Engdahl, Full Spectrum Dominance: Totalitarian Democracy in the New World Order, Wiesbaden, edition.engdahl, October 2009, p.3. |

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)

Tectonic Shift in Heartland Power: Part II

Tectonic Shift in Heartland Power: Part II  After the 2004 Ukraine Orange Revolution, Moscow’s western pipeline strategy until now has been to bypass both Ukraine and Poland through construction of an underwater gas pipeline, Nord Stream, running from Russia directly to Germany. Poland’s Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski is a Washington trained neo-conservative . As the previous Defense Minister, he played a central role in Poland’s missile defense agreement with Washington. Sikorski’s Poland today is bound closely to NATO, including agreeing to Washington’s militarily provocative missile deployment policies, and he is trying at every turn, so far unsuccessfully, to block construction of Nord Stream.

After the 2004 Ukraine Orange Revolution, Moscow’s western pipeline strategy until now has been to bypass both Ukraine and Poland through construction of an underwater gas pipeline, Nord Stream, running from Russia directly to Germany. Poland’s Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski is a Washington trained neo-conservative . As the previous Defense Minister, he played a central role in Poland’s missile defense agreement with Washington. Sikorski’s Poland today is bound closely to NATO, including agreeing to Washington’s militarily provocative missile deployment policies, and he is trying at every turn, so far unsuccessfully, to block construction of Nord Stream. All potential gas suppliers to the US-backed Nabucco pipeline to the EU are in doubt as Moscow outflanks USA

All potential gas suppliers to the US-backed Nabucco pipeline to the EU are in doubt as Moscow outflanks USA