| NSPM in English | |||

Аnother dubious provision in the Lisbon treaty: citizens' initiatives |

|

|

|

| петак, 15. јануар 2010. | |

|

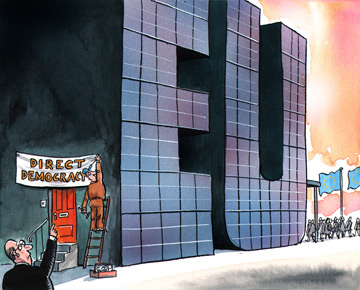

(The Economist print edition, 14.01.2010) GIVEN the chance, would European Union voters ban minarets on mosques, copying the recent popular vote in Switzerland? Invite citizens to draft new EU legislation, and would they demand new rights for the disabled, cleaner rivers and more aid for the developing world? Or are Europeans in a sour, recession-struck mood: would they seek tighter curbs on immigration, protectionist tariffs on Chinese imports, or new hurdles to EU enlargement (bye-bye, Turkey)?

The guessing will soon be over. Thanks to a barely debated clause in the Lisbon treaty, the EU is about to embark on an experiment in direct democracy. Within a year, the European Citizens’ Initiative will come into effect. One million EU citizens from a “significant number” of countries will be able to ask the European Commission to put forward new draft laws. As with so many bits of the Lisbon treaty, which came into force in December, it is not clear how the citizens’ initiative will work in practice, or even if it is a good idea. Euro-cheerleaders spent years banging on about the need for Lisbon, saying its new rules would make Europe simpler, more efficient and more democratic. Now they have the treaty, many of the same people are muttering and wailing about unresolved problems hidden in its leaden prose. Interview senior Brussels types about Lisbon, and the same phrases come up again and again: “we have no idea how this bit will work” and “of course, national leaders had no real idea what they were signing.” So it is with the citizens’ initiative, an idea adopted in the final days of a grandiose convention drawing up what was then called an EU constitution (becoming the Lisbon treaty after many misadventures). It was embraced without enthusiasm by ministers, national parliamentarians and members of the European Parliament, as the third choice of direct-democracy advocates. Their real dreams were binding, EU-wide referendums or, failing that, Californian-style popular initiatives that could lead to binding referendums, recalls Alain Lamassoure, a French MEP behind the plans. The convention rejected the first two options out of hand—“it was a sort of corporatist reaction, as we would say in France. Members of parliaments don’t like direct democracy,” says Mr Lamassoure. The initiative seemed harmless: it can only place an idea on the agenda, not actually oblige the commission to do anything (nothing came from a million-plus signatures on a petition calling for an end to the parliament’s monthly meandering from Brussels to Strasbourg). National governments and the European Parliament must now draw up rules that will decide if an initiative is easy or hard to pull off. One million is about 0.2% of the EU population. That is a low bar by European standards. In Switzerland federal initiatives need about 2% of the population to trigger a national vote. In Austria and Spain some 1.2% of the population must support a successful initiative. They must also decide how quickly signatures must be collected (time limits range from 30 days in Latvia to 18 months in Switzerland), and how—in town halls, or online? Publicly, Eurocrats are keen on the citizens’ initiative, hailing it as a way of injecting more democracy into the EU. Their private views are more pungent. Some senior commission officials fret about a ticking time-bomb of populism, waiting to be triggered by special-interest groups. Such sceptical euro-mandarins favour rules demanding that at least 0.2% of voters in any given country back an initiative, in at least a third of the EU’s members (ie, nine countries). Some governments see the citizens’ initiative as a gussied-up form of petition, and favour loose rules. Britain’s Europe minister, Chris Bryant, compares it to the petitions that can now be posted on the Downing Street website (these include petitions about British military post offices and child-care vouchers). Mr Bryant says the government disagrees with many Downing Street e-petitions (such as, presumably, one last year that called for Gordon Brown to resign), but those in power should “grow up” and be prepared to defend their arguments. Not for the first time, supporters of deeper EU integration hope that governments have unwittingly agreed to something that is potentially revolutionary. They hail the citizens’ initiative as a step towards creating a “European demos”, or a democratic debate that crosses borders. Such integrationists think the European Parliament has failed to solve the EU’s democratic deficit because national parties still control it. For them, the real goal is pan-European parties mounting pan-European election campaigns, in which voters choose not just MEPs but also the commission’s president (with each big political group nominating a candidate to run the commission ahead of the elections). As a first step, the citizens’ initiative carries risks of populism, concedes Mr Lamassoure, but it is worth having if it “helps with the birth of true European political networks”. What next? A lot of ideas will go nowhere, not least because initiatives can ask the commission to legislate only if the EU has the legal right to act. It has no powers to ban minarets, for example. Nor will it become the next California, voting for budget-busting tax cuts: the union has only marginal powers over indirect tax rates. But many populist initiatives will fall within the commission’s legal powers: caps on legal migration, for example, or a ban on genetically modified organisms (a prime candidate for an early initiative). If the commission thinks such initiatives are dangerous, it may decline to act, though then it will have to explain why it has ignored a million signatures. Moreover, even if the commission says yes, national governments and the European Parliament might say no, leaving citizens fuming. It could get messy, in short. But then democracy is messy. |

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)